Hotline: 0906 201 222

Đề thi thử IELTS Reading như thế nào? Những chủ đề nào đã được ra nhiều nhất năm nay? Bài viết này này sẽ tổng hợp đề thi IELTS Reading thật nhất, mới nhất (update liên tục) mà Aland đã tổng hợp, chia sẻ với các bạn để nắm được hướng ra đề và thực hành tốt hơn nhé.

Aland IELTS xin giới thiệu với tất cả các bạn bộ đề thi IELTS Reading mới nhất (update liên tục), có kèm đáp án chi tiết ở cuối bài. Dành cho những bạn nào muốn làm quen hoặc nâng cao trình độ của mình trong bài thi IELTS Reading.

Nếu bạn là người mới bắt đầu, hay chưa biết nhiều về các dạng bài trong đề thi IELTS Reading thì không nên vội vàng làm đề. Hãy tham khảo ngay các bài viết sau đây để nắm vững những kiến thức cơ bản để chuẩn bị tốt nhất cho bài thi này:

THE IMPORTANCE OF CHILDREN'S PLAY

Brick by brick, six-year-old Alice is building a magical kingdom. Imagining fairy-tale turrets and fire-breathing dragons, wicked witches and gallant heroes, she's creating an enchanting world. Although she isn't aware of it, this fantasy is helping her take her first steps towards her capacity for creativity and so it will have important repercussions in her adult life.

Minutes later, Alice has abandoned the kingdom in favour of playing schools with her younger brother. When she bosses him around as his 'teacher', she's practising how to regulate her emotions through pretence. Later on, when they tire of this and settle down with a board game, she's learning about the need to follow rules and take turns with a partner.

'Play in all its rich variety is one of the highest achievements of the human species,' says Dr David Whitebread from the Faculty of Education at the University of Cambridge, UK. 'It underpins how we develop as intellectual, problem-solving adults and is crucial to our success as a highly adaptable species.'

Recognising the importance of play is not new: over two millennia ago, the Greek philosopher Plato extolled its virtues as a means of developing skills for adult life, and ideas about play-based learning have been developing since the 19th century.

But we live in changing times, and Whitebread is mindful of a worldwide decline in play, pointing out that over half the people in the world now live in cities. 'The opportunities for free play, which I experienced almost every day of my childhood, are becoming increasingly scarce,' he says. Outdoor play is curtailed by perceptions of risk to do with traffic, as well as parents' increased wish to protect their children from being the victims of crime, and by the emphasis on 'earlier is better' which is leading to greater competition in academic learning and schools.

International bodies like the United Nations and the European Union have begun to develop policies concerned with children's right to play, and to consider implications for leisure facilities and educational programmes. But what they often lack is the evidence to base policies on.

'The type of play we are interested in is child-initiated, spontaneous and unpredictable- but, as soon as you ask a five-year-old "to play", then you as the researcher have intervened,' explains Dr Sara Baker. 'And we want to know what the long-term impact of play is. It's a real challenge.'

Dr Jenny Gibson agrees, pointing out that although some of the steps in the puzzle of how and why play is important have been looked at, there is very little data on the impact it has on the child's later life.

Now, thanks to the university's new Centre for Research on Play in Education, Development and Learning (PEDAL), Whitebread, Baker, Gibson and a team of researchers hope to provide evidence on the role played by play in how a child develops.

'A strong possibility is that play supports the early development of children's self-control,' explains Baker. 'This is our ability to develop awareness of our own thinking processes - it influences how effectively we go about undertaking challenging activities.'

In a study carried out by Baker with toddlers and young pre-schoolers, she found that children with greater self-control solved problems more quickly when exploring an unfamiliar set-up requiring scientific reasoning. 'This sort of evidence makes us think that giving children the chance to play will make them more successful problem-solvers in the long run.'

If playful experiences do facilitate this aspect of development, say the researchers, it could be extremely significant for educational practices, because the ability to self-regulate has been shown to be a key predictor of academic performance.

Gibson adds: 'Playful behaviour is also an important indicator of healthy social and emotional development. In my previous research, I investigated how observing children at play can give us important clues about their well-being and can even be useful in the diagnosis of neurodevelopmental disorders like autism.'

Whitebread's recent research has involved developing a play-based approach to supporting children's writing. 'Many primary school children find writing difficult, but we showed in a previous study that a playful stimulus was far more effective than an instructional one.' Children wrote longer and better-structured stories when they first played with dolls representing characters in the story. In the latest study, children first created their story with Lego*, with similar results. 'Many teachers commented that they had always previously had children saying they didn't know what to write about. With the Lego building, however, not a single child said this through the whole year of the project.'

Whitebread, who directs PEDAL, trained as a primary school teacher in the early 1970s, when, as he describes, 'the teaching of young children was largely a quiet backwater, untroubled by any serious intellectual debate or controversy.' Now, the landscape is very different, with hotly debated topics such as school starting age.

'Somehow the importance of play has been lost in recent decades. It's regarded as something trivial, or even as something negative that contrasts with "work". Let's not lose sight of its benefits, and the fundamental contributions it makes to human achievements in the arts, sciences and technology. Let's make sure children have a rich diet of play experiences.'

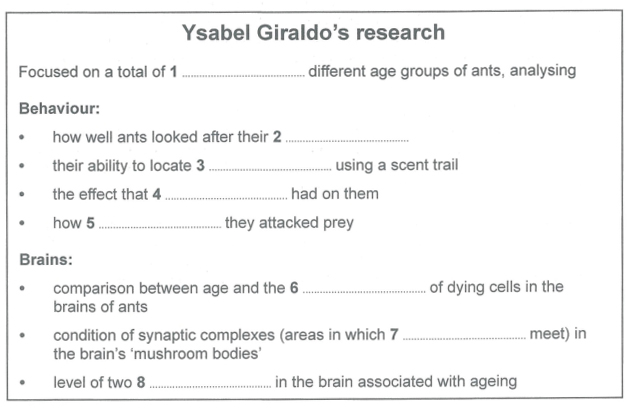

Complete the notes below.

Write ONLY ONE WORD for each answer.

Write your answer in boxes 1-8 on your answer sheet.

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 1?

In boxes 9-13 on your answer sheet, write

| TRUE | if the statement is true |

| FALSE | if the statement is false |

| NOT GIVEN | if the information is not given in the passage |

9. Children with good self-control are known to be likely to do well at school later on

10. The way a child plays may provide information about possible medical problems

11. Playing with dolls was found to benefit girls' writing more than boys' writing

12. Children had problems thinking up ideas when they first created the story with Lego

13. People nowadays regard children's play as less significant than they did in the past

⇨ 9 Tips học IELTS Reding hiệu quả

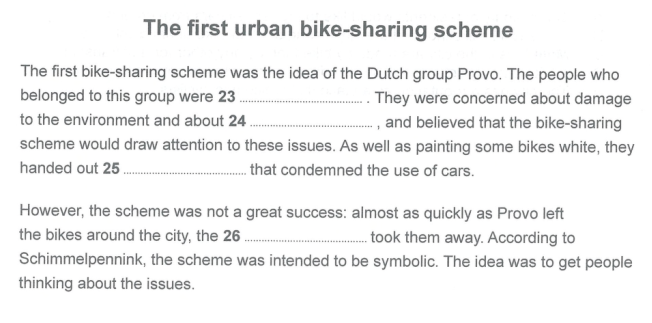

How Dutch engineer Luud Schimmelpennink helped to devise urban bike-sharing schemes

A. The original idea for an urban bike-sharing scheme dates back to a summer's day in Amsterdam in 1965. Provo, the organisation that came up with the idea, was a group of Dutch activists who wanted to change society. They believed the scheme, which was known as the Witte Fietsenplan, was an answer to the perceived threats of air pollution and consumerism. In the centre of Amsterdam, they painted a small number of used bikes white. They also distributed leaflets describing the dangers of cars and inviting people to use the white bikes. The bikes were then left unlocked at various locations around the city, to be used by anyone in need of transport.

B. Luud Schimmelpennink, a Dutch industrial engineer who still lives and cycles in Amsterdam, was heavily involved in the original scheme. He recalls how the scheme succeeded in attracting a great deal of attention - particularly when it came to publicising Provo's aims - but struggled to get off the ground. The police were opposed to Provo's initiatives and almost as soon as the white bikes were distributed around the city, they removed them. However, for Schimmelpennink and for bike-sharing schemes in general, this was just the beginning. 'The first Witte Fietsenplan was just a symbolic thing,' he says. 'We painted a few bikes white, that was all. Things got more serious when I became a member of the Amsterdam city council two years later.'

C. Schimmelpennink seized this opportunity to present a more elaborate Witte Fietsenplan to the city council. 'My idea was that the municipality of Amsterdam would distribute 10,000 white bikes over the city, for everyone to use,' he explains. 'I made serious calculations. It turned out that a white bicycle - per person, per kilometre - would cost the municipality only 10% of what it contributed to public transport per person per kilometre.' Nevertheless, the council unanimously rejected the plan. 'They said that the bicycle belongs to the past. They saw a glorious future for the car,' says Schimmelpennink. But he was not in the least discouraged.

D. Schimmelpennink never stopped believing in bike-sharing, and in the mid-90s, two Danes asked for his help to set up a system in Copenhagen. The result was the world's first large-scale bike-share programme. It worked on a deposit: 'You dropped a coin in the bike and when you returned it, you got your money back.' After setting up the Danish system, Schimmelpennink decided to try his luck again in the Netherlands - and this time he succeeded in arousing the interest of the Dutch Ministry of Transport. 'Times had changed,' he recalls. 'People had become more environmentally conscious, and the Danish experiment had proved that bike-sharing was a real possibility.' A new Witte Fietsenplan was launched in 1999 in Amsterdam. However, riding a white bike was no longer free; it cost one guilder per trip and payment was made with a chip card developed by the Dutch bank Postbank. Schimmelpennink designed conspicuous, sturdy white bikes locked in special racks which could be opened with the chip card- the plan started with 250 bikes, distributed over five stations.

E. Theo Molenaar, who was a system designer for the project, worked alongside Schimmelpennink. 'I remember when we were testing the bike racks, he announced that he had already designed better ones. But of course, we had to go through with the ones we had.' The system, however, was prone to vandalism and theft. 'After every weekend there would always be a couple of bikes missing,' Molenaar says. 'I really have no idea what people did with them, because they could instantly be recognised as white bikes.' But the biggest blow came when Postbank decided to abolish the chip card, because it wasn't profitable. 'That chip card was pivotal to the system,' Molenaar says. 'To continue the project we would have needed to set up another system, but the business partner had lost interest.'

F. Schimmelpennink was disappointed, but- characteristically- not for long. In 2002 he got a call from the French advertising corporation JC Decaux, who wanted to set up his bike-sharing scheme in Vienna. 'That went really well. After Vienna, they set up a system in Lyon. Then in 2007, Paris followed. That was a decisive moment in the history of bike-sharing.' The huge and unexpected success of the Parisian bike-sharing programme, which now boasts more than 20,000 bicycles, inspired cities all over the world to set up their own schemes, all modelled on Schimmelpennink's. 'It's wonderful that this happened,' he says. 'But financially I didn't really benefit from it, because I never filed for a patent.'

G. In Amsterdam today, 38% of all trips are made by bike and, along with Copenhagen, it is regarded as one of the two most cycle-friendly capitals in the world - but the city never got another Witte Fietsenplan. Molenaar believes this may be because everybody in Amsterdam already has a bike. Schimmelpennink, however, cannot see that this changes Amsterdam's need for a bike-sharing scheme. 'People who travel on the underground don't carry their bikes around. But often they need additional transport to reach their final destination.' Although he thinks it is strange that a city like Amsterdam does not have a successful bike sharing scheme, he is optimistic about the future. 'In the '60s we didn't stand a chance because people were prepared to give their lives to keep cars in the city. But that mentality has totally changed. Today everybody longs for cities that are not dominated by cars.'

Reading Passage 2 has seven paragraphs, A- G

Which paragraph contains the following information?

Write the correct letter, A-G, in boxes 14-18 on your answer sheet.

NB You may use any letter more than once.

14. a description of how people misused a bike-sharing scheme

15. an explanation of why a proposed bike-sharing scheme was turned down

16. a reference to a person being unable to profit from their work

17. an explanation of the potential savings a bike-sharing scheme would bring

18. a reference to the problems a bike-sharing scheme was intended to solve

Choose TWO letters, A-E.

Write the correct letters

in boxes 19 and 20 on your answer sheet.

Which TWO of the following statements are made in the text about the

Amsterdam bike-sharing scheme of 1999?

A It was initially opposed by a government department.

B It failed when a partner in the scheme withdrew support.

C It aimed to be more successful than the Copenhagen scheme.

D it was made possible by a change in people's attitudes.

E It attracted interest from a range of bike designers.

Choose TWO letters, A-E.

Write the correct letters in boxes 21 and 22 on your answer sheet.

Which TWO of the following statements are made in the text about Amsterdam today?

A The majority of residents would like to prevent all cars from entering the city.

B There is little likelihood of the city having another bike-sharing scheme.

C More trips in the city are made by bike than by any other form of transport

D A bike-sharing scheme would benefit residents who use public transport.

E The city has a reputation as a place that welcomes cyclists.

Complete the summary below.

Choose ONE WORD ONLY from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 23-26 on your answer sheet.

A critical ingredient in the success of hotels is developing and maintaining superior performance from their employees. How is that accomplished? What Human Resource Management (HRM) practices should organizations invest in to acquire and retain great employees?

Some hotels aim to provide superior working conditions for their employees. The idea originated from workplaces - usually in the non-service sector - that emphasized fun and enjoyment as part of work-life balance. By contrast, the service sector, and more specifically hotels, has traditionally not extended these practices to address basic employee needs, such as good working conditions.

Pfeffer (1994) emphasizes that in order to succeed in a global business environment, organizations must make investment in Human Resource Management (HRM) to allow them to acquire employees who possess better skills and capabilities than their competitors. This investment will be to their competitive advantage. Despite this recognition of the importance of employee development, the hospitality industry has historically been dominated by underdeveloped HR practices (Lucas, 2002).

Lucas also points out that 'the substance of HRM practices does not appear to be designed to foster constructive relations with employees or to represent a managerial approach that enables developing and drawing out the full potential of people, even though employees may be broadly satisfied with many aspects of their work' (Lucas, 2002). In addition, or maybe as a result, high employee turnover has been a recurring problem throughout the hospitality industry. Among the many cited reasons are low compensation, inadequate benefits, poor working conditions and compromised employee morale and attitudes (Maroudas et al., 2008).

Ng and Sorensen (2008) demonstrated that when managers provide recognition to employees, motivate employees to work together, and remove obstacles preventing effective performance, employees feel more obligated to stay with the company. This was succinctly summarized by Michel et al. (2013): '[P]roviding support to employees gives them the confidence to perform their jobs better and the motivation to stay with the organization.' Hospitality organizations can therefore enhance employee motivation and retention through the development and improvement of their working conditions. These conditions are inherently linked to the working environment.

While it seems likely that employees' reactions to their job characteristics could be affected by a predisposition to view their work environment negatively, no evidence exists to support this hypothesis (Spector et al., 2000). However, given the opportunity, many people will find something to complain about in relation to their workplace (Poulston, 2009). There is a strong link between the perceptions of employees and particular factors of their work environment that are separate from the work itself, including company policies, salary and vacations.

Such conditions are particularly troubling for the luxury hotel market, where high-quality service, requiring a sophisticated approach to HRM, is recognized as a critical source of competitive advantage (Maroudas et al., 2008). In a real sense, the services ofhotel employees represent their industry (Schneider and Bowen, 1993). This representation has commonly been limited to guest experiences. This suggests that there has been a dichotomy between the guest environment provided in luxury hotels and the working conditions of their employees.

It is therefore essential for hotel management to develop HRM practices that enable them to inspire and retain competent employees. This requires an understanding of what motivates employees at different levels of management and different stages of their careers (Enz and Siguaw, 2000). This implies that it is beneficial for hotel managers to understand what practices are most favorable to increase employee satisfaction and retention.

Herzberg (1966) proposes that people have two major types of needs, the first being extrinsic motivation factors relating to the context in which work is performed, rather than the work itself. These include working conditions and job security. When these factors are unfavorable, job dissatisfaction may result. Significantly, though, just fulfilling these needs does not result in satisfaction, but only in the reduction of dissatisfaction (Maroudas et al., 2008).

Employees also have intrinsic motivation needs or motivators, which include such factors as achievement and recognition. Unlike extrinsic factors, motivator factors may ideally result in job satisfaction (Maroudas et al., 2008). Herzberg's (1966) theory discusses the need for a 'balance' of these two types of needs.

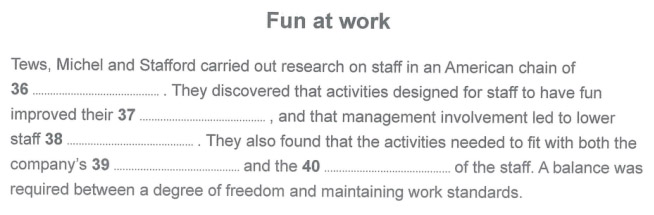

The impact of fun as a motivating factor at work has also been explored. For example, Tews, Michel and Stafford (2013) conducted a study focusing on staff from a chain of themed restaurants in the United States. It was found that fun activities had a favorable impact on performance and manager support for fun had a favorable impact in reducing turnover.Their findings support the view that fun may indeed have a beneficial effect, but the framing of that fun must be carefully aligned with both organizational goals and employee characteristics. 'Managers must learn how to achieve the delicate balance of allowing employees the freedom to enjoy themselves at work while simultaneously maintaining high levels of performance' (Tews et al., 2013).

Deery (2008) has recommended several actions that can be adopted at the organizational level to retain good staff as well as assist in balancing work and family life. Those particularly appropriate to the hospitality industry include allowing adequate breaks during the working day, staff functions that involve families, and providing health and well-being opportunities.

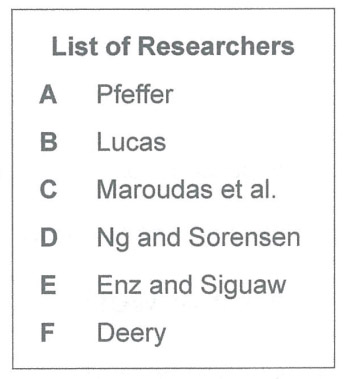

Look at the following statements (Questions 27-31) and the list of researchers below.

Match each statement with the correct researcher, A-F.

Write the correct letter, A-F, in boxes 27-31 on your answer

sheet.

NB You may use any letter more than once.

27. Hotel managers need to know what would encourage good staff to remain.

28. The actions of managers may make staff feel they shouldn't move to a different employer.

29. Little is done in the hospitality industry to help workers improve their skills.

30. Staff are less likely to change jobs if cooperation is encouraged.

31. Dissatisfaction with pay is not the only reason why hospitality workers change jobs.

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 3?

In boxes 32-35 on your answer sheet, write

| TRUE | if the statement is true |

| FALSE | if the statement is false |

| NOT GIVEN | if the information is not given in the passage |

32. One reason for high staff turnover in the hospitality industry is poor morale.

33. Research has shown that staff have a tendency to dislike their workplace.

34. An improvement in working conditions and job security makes staff satisfied with their jobs.

35. Staff should be allowed to choose when they take breaks during the working day

Choose ONE WORD ONLY from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 36-40 on your answer sheet.

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 1-13, which are based on Reading Passage 1 below.

THE CONCEPT OF INTELLIGENCE

A. Looked at in one way, everyone knows what intelligence is; looked at in another way, no one does. In other words, people all have unconscious notions - lmown as 'implicit theories' - of intelligence, but no one knows for certain what it actually is. This chapter addresses how people conceptualize intelligence, whatever it may actually be.

But why should we even care what people think intelligence is, as opposed only to valuing whatever it actually is? There are at least four reasons people's conceptions of intelligence matter.

B. First, implicit theories of intelligence drive the way in which people perceive and evaluate their own intelligence and that of others. To better understand the judgments people make about their own and others' abilities, it is useful to learn about people's implicit theories. For example, parents' implicit theories of their children's language development will determine at what ages they will be willing to make various corrections in their children's speech. More generally, parents' implicit theories of intelligence will determine at what ages they believe their children are ready to perform various cognitive tasks. Job interviewers will make hiring decisions on the basis of their implicit theories of intelligence. People will decide who to be friends with on the basis of such theories. In sum, knowledge about implicit theories of intelligence is important because this knowledge is so often used by people to make judgments in the course of their everyday lives.

C. Second, the implicit theories of scientific investigators ultimately give rise to their explicit theories. Thus it is useful to find out what these implicit theories are. Implicit theories provide a framework that is useful in defining the general scope of a phenomenon - especially a not-well-understood phenomenon. These implicit theories can suggest what aspects of the phenomenon have been more or less attended to in previous investigations.

D. Third, implicit theories can be useful when an investigator suspects that existing explicit theories are wrong or misleading. If an investigation of implicit theories reveals little correspondence between the extant implicit and explicit theories, the implicit theories may be wrong. But the possibility also needs to be taken into account that the explicit theories are wrong and in need of correction or supplementation. For example, some implicit theories of intelligence suggest the need for expansion of some of our explicit theories of the construct.

E. Finally, understanding implicit theories of intelligence can help elucidate developmental and cross-cultural differences. As mentioned earlier, people have expectations for intellectual performances that differ for children of different ages. How these expectations differ is in part a function of culture. For example, expectations for children who participate in Western-style schooling are almost certain to be different from those for children who do not participate in such schooling.

F. I have suggested that there are three major implicit theories of how intelligence relates to society as a whole (Sternberg, 1997). These might be called Hamiltonian, Jeffersonian, and Jacksonian. These views are not based strictly, but rather, loosely, on the philosophies of Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, and Andrew Jackson, three great statesmen in the history of the United States.

G. The Hamiltonian view, which is similar to the Platonic view, is that people are born with different levels of intelligence and that those who are less intelligent need the good offices of the more intelligent to keep them in line, whether they are called government officials or, in Plato's term, philosopher-kings. Herrnstein and Murray (1994) seem to have shared this belief when they wrote about the emergence of a cognitive (high-IQ) elite, which eventually would have to take responsibility for the largely irresponsible masses of non-elite (low-IQ) people who cannot take care of themselves. Left to themselves, the unintelligent would create, as they always have created, a kind of chaos.

H. The Jeffersonian view is that people should have equal opportunities, but they do not necessarily avail themselves equally of these opportunities and are not necessarily equally rewarded for their accomplishments. People are rewarded for what they accomplish, if given equal opportunity. Low achievers are not rewarded to the same extent as high achievers.

I. In the Jeffersonian view, the goal of education is not to favor or foster an elite, as in the Hamiltonian tradition, but rather to allow children the opportunities to make full use of the skills they have. My own views are similar to these (Sternberg, 1997). The Jacksonian view is that all people are equal, not only as human beings but in terms of their competencies -that one person would serve as well as another in government or on a jury or in almost any position of responsibility. In this view of democracy, people are essentially intersubstitutable except for specialized skills, all of which can be learned. In this view, we do not need or want any institutions that might lead to favoring one group over another.

J. Implicit theories of intelligence and of the relationship of intelligence to society perhaps need to be considered more carefully than they have been because they often serve as underlying presuppositions for explicit theories and even experimental designs that are then taken as scientific contributions. Until scholars are able to discuss their implicit theories and thus their assumptions, they are likely to miss the point of what others are saying when discussing their explicit theories and their data.

Reading Passage 1 has ten sections, A-J.

Which section contains the following information?

Write the correct letter, A-J in boxes 1-3 on your answer sheet.

1. information about how non-scientists' assumptions about intelligence influence their behaviour

2. a reference to lack of clarity over the definition of intelligence

3. a point that a researcher's implicit and explicit theories may be very different

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 1?

In boxes 4-6 on your answer sheet, write

| TRUE | if the statement is true |

| FALSE | if the statement is false |

| NOT GIVEN | if the information is not given in the passage |

4. Slow language development in children is likely to prove disappointing to their parents.

5. People's expectation of what children should gain form education are universal.

6. Scholar may discuss theories without fully understanding each other.

Look at the following statements (Questions 7-13) and the list of theories below.

Match each statement with the correct theory, A, B, or C.

Write the correct letter, A, B, or C, in boxes 7-13 on your answer sheet.

NB You may use any letter more than once.

7. It is desirable for the same possibilities to be open to everyone.

A Hamiltonian

B Jeffersonian

C Jacksonian

8. No section of society should have preferential treatment at the expense of another.

A Hamiltonian

B Jeffersonian

C Jacksonian

9. People should only gain benefits on the basis of what they actually achieve.

A Hamiltonian

B Jeffersonian

C Jacksonian

10. Variation in intelligence begins at birth.

A Hamiltonian

B Jeffersonian

C Jacksonian

11. The more intelligent people should be in positions of power.

A Hamiltonian

B Jeffersonian

C Jacksonian

12. Everyone can develop the same abilities.

A Hamiltonian

B Jeffersonian

C Jacksonian

13. People of low intelligence are likely to lead uncontrolled lives.

A Hamiltonian

B Jeffersonian

C Jacksonian

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 14-26, which are based on Reading Passage 2 below.

SAVING BUGS TO FIND NEW DRUGS

Zoologist Ross Piper looks at the potential of insects in pharmaceutical reseach

A. More drugs than you might think are derived from, or inspired by, compounds found in living things. Looking to nature for the soothing and curing of our ailments is nothing new - we have been doing it for tens of thousands of years. You only have to look at other primates - such as the capuchin monkeys who rub themselves with toxin-oozing millipedes to deter mosquitoes, or the chimpanzees who use noxious forest plants to rid themselves of intestinal parasites - to realise that our ancient ancestors too probably had a basic grasp of medicine.

B. Pharmaceutical science and chemistry built on these ancient foundations and perfected the extraction, characterisation, modification and testing of these natural products. Then, for a while, modern pharmaceutical science moved its focus away from nature and into the laboratory, designing chemical compounds from scratch. The main cause of this shift is that although there are plenty of promising chemical compounds in nature, finding them is far from easy. Securing sufficient numbers of the organism in question, isolating and characterising the compounds of interest, and producing large quantities of these compounds are all significant hurdles.

C. Laboratory-based drug discovery has achieved varying levels of success, something which has now prompted the development of new approaches focusing once again on natural products. With the ability to mine genomes for useful compounds, it is now evident that we have barely scratched the surface of nature's molecular diversity. This realisation, together with several looming health crises, such as antibiotic resistance, has put bioprospecting - the search for useful compounds in nature - firmly back on the map.

D. Insects are the undisputed masters of the terrestrial domain, where they occupy every possible niche. Consequently, they have a bewildering array of interactions with other organisms, something which has driven the evolution of an enormous range of very interesting compounds for defensive and offensive purposes. Their remarkable diversity exceeds that of every other group of animals on the planet combined. Yet even though insects are far and away the most diverse animals in existence, their potential as sources of therapeutic compounds is yet to be realised.

E. From the tiny proportion of insects that have been investigated, several promising compounds have been identified. For example, alloferon, an antimicrobial compound produced by blow fly larvae, is used as an antiviral and antitumor agent in South Korea and Russia. The larvae of a few other insect species are being investigated for the potent antimicrobial compounds they produce. Meanwhile, a compound from the venom of the wasp Polybia paulista has potential in cancer treatment.

F. Why is it that insects have received relatively little attention in bioprospecting?Firstly, there are so many insects that, without some manner of targeted approach, investigating this huge variety of species is a daunting task. Secondly, insects are generally very small, and the glands inside them that secrete potentially useful compounds are smaller still. This can make it difficult to obtain sufficient quantities of the compound for subsequent testing. Thirdly, although we consider insects to be everywhere, the reality of this ubiquity is vast numbers of a few extremely common species. Many insect species are infrequently encountered and very difficult to rear in captivity, which, again, can leave us with insufficient material to work with.

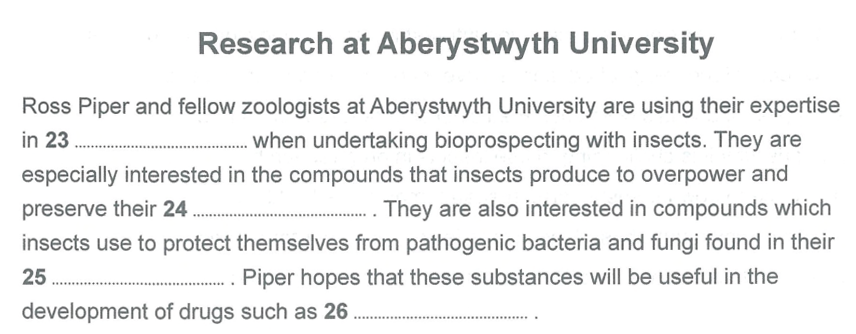

G. My colleagues and I at Aberystwyth University in the UK have developed an approach in which we use our knowledge of ecology as a guide to target our efforts. The creatures that particularly interest us are the many insects that secrete powerful poison for subduing prey and keeping it fresh for future consumption. There are even more insects that are masters of exploiting filthy habitats, such as faeces and carcasses, where they are regularly challenged by thousands of microorganisms. These insects have many antimicrobial compounds for dealing with pathogenic bacteria and fungi, suggesting that there is certainly potential to find many compounds that can serve as or inspire new antibiotics.

H. Although natural history knowledge points us in the right direction, it doesn't solve the problems associated with obtaining useful compounds from insects. Fortunately, it is now possibleto snip out the stretches of the insect's DNA that carry the codes for the interesting compounds and insert them into cell lines that allow larger quantities to be produced. And although the road from isolating and characterising compounds with desirable qualities to developing a commercial product is very long and full of pitfalls, the variety of successful animal-derived pharmaceuticals on the market demonstrates there is a precedent here that is worth exploring.

I. With every bit of wilderness that disappears, we deprive ourselves of potential medicines. As much as I'd love to help develop a groundbreaking insect-derived medicine, my main motivation for looking at insects in this way is conservation. I sincerely believe that all species, however small and seemingly insignificant, have a right to exist for their own sake. If we can shine a light on the darker recesses of nature's medicine cabinet, exploring the useful chemistry of the most diverse animals on the planet, I believe we can make people think differently about the value of nature.

Reading Passage 2 has ten sections, A-J.

Which section contains the following information?

Write the correct letter, A-J in boxes 14-20 on your answer sheet.

14. mention of factors driving a renewed interest in natural medicinal compounds

15. how recent technological advances have made insect research easier

16. examples of animals which use medicinal substances from nature

17. reasons why it is challenging to use insects in drug research

18. reference to how interest in drug research may benefit wildlife

19. a reason why nature-based medicines fell out of favour for a period

20. an example of an insect-derived medicine in use at the moment

Choose TWO letters, A-E.

Write the correct letters in boxes 21 and 22 on your answer sheet.

Which TWO of the following make insects interesting for drug research?

A. the huge number of individual insects in the world

B. the variety of substances insects have developed to protect themselves

C. the potential to extract and make use of insects' genetic codes

D. the similarities between different species of insect

E. the manageable size of most insects

Choose ONE WORD ONLY from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 23-26 on your answer sheet.

THE POWER OF PLAY

Virtually every child, the world over, plays. The drive to play is so intense that children will do so in any circumstances, for instance when they have no real toys, or when parents do not actively encourage the behavior. In the eyes of a young child, nmning, pretending, and building are fun. Researchers and educators know that these playful activities benefit the development of the whole child across social, cognitive, physical, and emotional domains. Indeed, play is such an instrumental component to healthy child development that the United Nations High Commission on Human Rights (1989) recognized play as a fundamental right of every child.

Yet, while experts continue to expound a powerful argument for the importance of play in children's lives, the actual time children spend playing continues to decrease. Today, children play eight hours less each week than their counterparts did two decades ago (Elkind 2008). Under pressure of rising academic standards, play is being replaced by test preparation in kindergartens and grade schools, and parents who aim to give their preschoolers a leg up are led to believe that flashcards and educational 'toys' are the path to success. Our society has created a false dichotomy between play and learning.

Through play, children learn to regulate their behavior, lay the foundations for later learning in science and mathematics, figure out the complex negotiations of social relationships, build a repertoire of creative problem-solving skills, and so much more. There is also an important role for adults in guiding children through playful learning opportunities.

Full consensus on a formal definition of play continues to elude the researchers and theorists who study it. Definitions range from discrete descriptions of various types of play such as physical, construction, language, or symbolic play (Miller & Almon 2009), to lists of broad criteria, based on observations and attitudes, that are meant to capture the essence of all play behaviors ( e.g. Rubin et al. 1983).

A majority of the contemporary definitions of play focus on several key criteria. The founder of the National Institute for Play, Stuart Brown, has described play as 'anything that spontaneously is done for its own sake'. More specifically, he says it 'appears purposeless, produces pleasure and joy, [ and] leads one to the next stage of mastery' ( as quoted in Tippett 2008). Similarly, Miller and Almon (2009) say that play includes 'activities that are freely chosen and directed by children and arise from intrinsic motivation'. Often, play is defined along a continuum as more or less playful using the following set of behavioral and dispositional criteria (e.g. Rubin et al. 1983):

Play is pleasurable: Children must enjoy the activity or it is not play. It is intrinsically motivated: Children engage in play simply for the satisfaction the behavior itself brings. It has no extrinsically motivated function or goal. Play is process oriented: When children play, the means are more important than the ends. It is freely chosen, spontaneous and voluntary. If a child is pressured, they will likely not think of the activity as play. Play is actively engaged: Players must be physically and/or mentally involved in the activity. Play is non-literal. It involves make-believe.

According to this view, children's playful behaviors can range in degree from 0% to 100% playful. Rubin and colleagues did not assign greater weight to any one dimension in determining playfulness; however, other researchers have suggested that process orientation and a lack of obvious functional purpose may be the most important aspects of play ( e.g. Pellegrini 2009).

From the perspective of a continuum, play can thus blend with other motives and attitudes that are less playful, such as work. Unlike play, work is typically not viewed as enjoyable and it is extrinsically motivated (i.e. it is goal oriented. Researcher Joan Goodman (1994) suggested that hybrid forms of work and play are not a detriment to learning; rather, they can provide optimal contexts for learning. For example, a child may be engaged in a difficult, goal-directed activity set up by their teacher, but they may still be actively engaged and intrinsically motivated. At this mid-point between play and work, the child's motivation, coupled with guidance from an adult, can create robust opportunities for playful learning.

Critically, recent research supports the idea that adults can facilitate children's learning while maintaining a playful approach in interactions known as 'guided play' (Fisher et al. 2011). The adult's role in play varies as a function of their educational goals and the child's developmental level (Hirsch-Pasek et al. 2009).

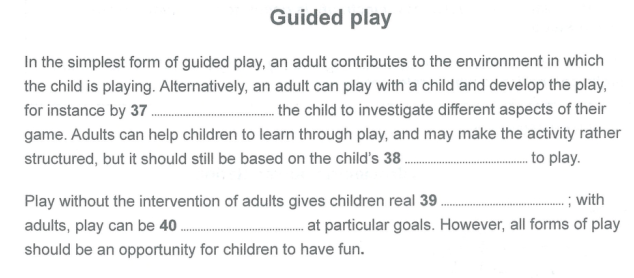

Guided play takes two forms. At a very basic level, adults can enrich the child's environment by providing objects or experiences that promote aspects of a curriculum. In the more direct form of guided play, parents or other adults can support children's play by joining in the fun as a co-player, raising thoughtful questions, commenting on children's discoveries, or encouraging further exploration or new facets to the child's activity. Although playful learning can be somewhat structured, it must also be child-centered (Nicolopolou et al. 2006). Play should stem from the child's own desire.

Both free and guided play are essential elements in a child-centered approach to playful learning. Intrinsically motivated free play provides the child with true autonomy, while guided play is an avenue through which parents and educators can provide more targeted learning experiences. In either case, play should be actively engaged, it should be predominantly child-directed, and it must be fun.

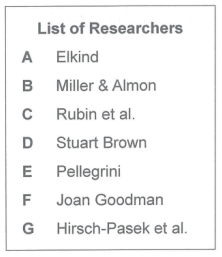

Look at the following statements (Questions 27-31) and the list of researchers below.

Match each statement with the correct researcher, A-G

Write the correct letter, A-G, in boxes 27-31 on your answer sheet.

27. Play can be divided into a number of separate categories.

28. Adults' intended goals affect how they play with children.

29. Combining work with play may be the best way for children to learn.

30. Certain elements of play are more significant than others.

31. Activities can be classified on a scale of playfulness.

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 3?

In boxes 32-36 on your answer sheet, write

| TRUE | if the statement is true |

| FALSE | if the statement is false |

| NOT GIVEN | if the information is not given in the passage |

32. Children need toys in order to play.

33. It is a mistake to treat play and learning as separate types of activities.

34. Play helps children to develop their artistic talents.

35. Researchers has agreed on a definition of play.

36. Work and play differ in term of whether or not they have a taget.

Choose ONE WORD ONLY from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 37-40 on your answer sheet.

|

► Để tải đáp án chi tiết của bộ đề thi IELTS Reading, click ngay TẠI ĐÂY |

Đồng thời không nên bỏ qua những tài liệu luyện thi IELTS Reading hay nhất dưới đây để nâng cao trình độ IELTS Reading của mình và đạt điểm sô cao hơn trong kỳ thi sắp tới nhé.

Chúc các bạn ôn thi tốt!